Barriers to Health Care Access for Low Income Families: a Review of Literature.

Community-Based Healthcare for Migrants and Refugees: A Scoping Literature Review of Best Practices

1

Department of Hygiene, Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 115 27 Athens, Greece

2

Julius Eye for Wellness Sciences and Main Care, University Medical Eye Utrecht, Utrecht University, 3584 CG Utrecht, The Netherlands

3

Renaissance School of Medicine, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794-8434, U.s.a.

iv

Found of Human Sciences, Wadham Higher, University of Oxford, Oxford OX1 3PN, U.k.

v

Prolepsis Institute for Preventive Medicine and Ecology and Occupational Health, 151 21 Marousi, Greece

*

Author to whom correspondence should exist addressed.

Received: 21 February 2020 / Revised: 17 April 2020 / Accepted: 23 Apr 2020 / Published: 28 April 2020

Abstruse

Background: Strengthening community-based healthcare is a valuable strategy to reduce health inequalities and meliorate the integration of migrants and refugees into local communities in the European union. Notwithstanding, trivial is known about how to finer develop and run community-based healthcare models for migrants and refugees. Aiming at identifying the most-promising best practices, we performed a scoping review of the international bookish literature into constructive community-based healthcare models and interventions for migrants and refugees as office of the Mig-HealthCare projection. Methods: A systematic search in PubMed, EMBASE, and Scopus databases was conducted in March 2018 post-obit the PRISMA methodology. Data extraction from eligible publications included information on general study characteristics, a brief clarification of the intervention/model, and reported outcomes in terms of effectiveness and challenges. Subsequently, we critically assessed the available bear witness per type of healthcare service according to specific criteria to establish a shortlist of the most promising all-time practices. Results: In total, 118 academic publications were critically reviewed and categorized in the thematic areas of mental wellness (n = 53), general wellness services (n = 36), noncommunicable diseases (n = 13), primary healthcare (due north = ix), and women'due south maternal and kid health (n = seven). Determination: A set of xv of the virtually-promising best practices and tools in customs-based healthcare for migrants and refugees were identified that include several intervention approaches per thematic category. The elements of good communication, the linguistic barriers and the cultural differences, played crucial roles in the effective application of the interventions. The shut collaboration of the various stakeholders, the local communities, the migrant/refugee communities, and the partnerships is a primal element in the successful implementation of primary healthcare provision.

ane. Introduction

In contempo years, over 2,000,000 migrants and refugees have fled civil unrest and socioeconomic instability and come to Europe since 2014 in search of a ameliorate and safer future [1]. A large portion of these individuals have come up from the Heart East, fleeing conflicts such as the Syrian Civil War. Migrants and refugees worldwide often encounter substantial barriers to healthcare in their new home countries [2]. The World Wellness Organization in the 2018 "Written report on the health of refugees and migrants in the European Matrimony" [3] indicates that there are significant limitations to the accessibility and delivery of proper healthcare, as well as to the degree of effective communication. These limitations are mainly caused by differences in language, lack of cognition regarding available services, limited participation in the economic system, the healthcare system operability in each land, and the varying cultural attitudes and beliefs. Every bit such, migrant and refugee populations are at college risks of poverty and social exclusion. These barriers lead to inequitable access to healthcare, which is described as a fundamental human right. To reduce and prevent health inequalities amid migrants and refugees in Europe, local healthcare systems volition need to adjust to the specific needs of this population. There is evidence that integration into existing healthcare systems is promoted through tailored services at the level of local communities [4]. However, little is known on how to finer develop and run community-based healthcare models for migrants and refugees.

In an try to provide testify-based information and practical guidance to the wellness professionals working at the primary healthcare level primarily in the EU Member States, the Mig-HealthCare project was launched in May 2017 (www.mighealthcare.eu) [5], partially funded by the European Commission Consumer, Health, Agriculture and Nutrient Executive Agency (CHAFEA). The project's aim is to produce a roadmap to constructive customs-based healthcare models in society to improve physical and mental healthcare services, to back up the inclusion and participation of migrants and refugees in European communities, and to reduce health inequalities.

As part of the activities planned within this projection, a systematic search in scientific databases was conducted with the objective to identify constructive community-based healthcare models and interventions for migrants and refugees that could exist used every bit all-time practices.

We performed a comprehensive review based on a search of the international, peer-reviewed literature to place requirements, prerequisites, and concrete steps to pattern and implement community-based healthcare models serving migrants and refugees. The first step was to map the different models that are reported worldwide in the academic literature, along with their characteristics, core elements, and reported outcomes. Secondly, nosotros critically analyzed the effectiveness of the models and interventions by applying prespecified criteria. Thirdly, based on our critical analysis and criteria evaluation, a shortlist of potential best practices and tools was created. Our findings are intended to provide policy-makers and health service providers working with migrant and refugee populations the concrete steps to successfully develop strategies to address and prevent health inequalities and foster integration at the level of local communities in Europe.

One of the immediate challenges of this task was the controversy surrounding the terms community-based healthcare and community health. The terms are oft used in different contexts, and dissimilar countries may utilize the terms in different ways. Yet, we believe meaningful results tin can be obtained from a review of publications explicitly addressing customs-based models and interventions. For the purpose of this review, we use a broad conception of customs as "a group of inhabitants living in a somewhat localized area nether the aforementioned general regulations and having mutual norms, values, and organizations" [six]. Community health refers to the wellness condition of a divers grouping of people and the actions and weather condition, both private and public (governmental), to promote, protect, and preserve their health [7]. Migrant and refugees are terms that are oftentimes used interchangeably, but they are defined past the Un High Committee for Refugees (UNHCR) as follows [viii]: Migrants: "While at that place is no formal legal definition of an international migrant, well-nigh experts concur that an international migrant is someone who changes his or her country of usual residence, irrespective of the reason for migration or legal condition. Generally, a distinction is fabricated between short-term or temporary migration, covering movements with a duration between iii and 12 months, and long-term or permanent migration, referring to a modify of land of residence for a duration of one twelvemonth or more".

Refugees are "persons who are outside their country of origin for reasons of feared persecution, conflict, generalized violence, or other circumstances that have seriously disturbed public order and, every bit a consequence, require international protection. The refugee definition can exist institute in the 1951 Convention and regional refugee instruments, as well as UNHCR'southward Statute".

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection

A literature search was performed for articles published in the English language following the PRISMA statement [ix] in March 2018 in the databases: PubMed, EMBASE, and Scopus. Keywords and terms used were: "migrant", "immigrant", "refugee", "asylum-seeker", "healthcare", "community-based", and "model", combined with an "AND" and/or an "OR".

No limits for publication dates were set; however, nosotros divided our search in pre and postal service-2012 publication dates in an attempt to effectively capture data on the recent migrant/refugee influx into Europe after 2011 following the civil unrest in countries of the Centre Eastward and Africa, every bit our effort is of particular relevance to the present migrant/refugee crunch in Europe. Publications dated before 2012 have been published more often than not with respect to migrant/refugee populations in countries outside Europe, such as the Us and Australia, in years predating the current European influx of migrants and refugees from Africa and the Centre East.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Publications were eligible for review if they provided a comprehensive description of community-based models for healthcare delivery to migrant/refugee/asylum-seeking populations or other relevant minorities, every bit the provision of healthcare in some of these groups depends on legal condition. In our choice of relevant publications, nosotros employed a fairly broad concept of healthcare to deliberately cover different types of healthcare services and migrant/refugee population subgroups, such as adolescents, mothers, chronic patients, and migrants. This was done in society to produce a shortlist of potential best practices and tools covering the whole range of community-based health services so every bit to provide a broad base of data useful to policy-makers, researchers, and funders who work in this field. Eligibility was not restricted to models and interventions for specific groups of migrants and refugees. We included all ages, ethnicities, refugees, and migrants of whatsoever condition. Explicit mentioning of the terms "vulnerability" or "vulnerable" was non required for inclusion, every bit nosotros considered all migrants and refugees inherently vulnerable. All publications that proposed, discussed, or formally assessed a community-based model or intervention were included in the systematic drove and analysis. We excluded publications that merely reported on health needs, barriers, and challenges to healthcare access among migrants and refugees without containing the chemical element of specific practices and tools. Papers reporting on methods for participatory community-based wellness research, healthcare models strictly for rural or depression-resource areas, and papers on models to engage migrants in clinical research were also excluded. Abstracts and briefing proceedings were excluded from the formal analysis, equally an in-depth critical review was not possible to the aforementioned extent equally it was for full-text publications.

2.2. Data Extraction

For all articles included in the final assay, information was extracted on the following variables: (ane) total citation, (2) twelvemonth of publication, (iii) type of study/paper, (4) state of implementation, (4) target population, (5) type of care/health needs, (vi) model/intervention (keywords), (seven) basic characteristics of the model/intervention, (8) best practices, (9) lessons learned, and (x) challenges and limitations. For the critical appraisal, we too extracted data on: (11) mode of evaluation (according to study design); (12) duration of follow-upward (evaluation); (13) study sample (if applicable); and (14) theoretical underpinnings (e.thou., for interventions based on behavioral or other models related to perceptions, attitudes, and barriers to change habits). All 3054 identified manufactures were screened past three independent reviewers, and the results were jointly discussed.

To facilitate the analysis, the publications were grouped past indication/affliction area through an iterative process and, subsequently, categorized equally models or interventions for wellness promotion/education, prevention, or disease direction.

two.3. Disquisitional Assessment for Best Practices

Nosotros define "best practices" as interventions for which there is evidence to substantiate (at least some form of) effectiveness. To assess effectiveness, interventions described per category were evaluated based on the following criteria: study design; sample size; duration of follow-upwardly; whether the written report population was of Middle Eastern/North African descent (every bit this relates strongly to the increased influx of migrants/refugees into Europe post-obit the civil unrest in several countries in the area, such as Syria, Iraq, Great socialist people's libyan arab jamahiriya, and Lebanon); reported specific outcomes/advocate bear witness-based approach; presence of theoretical underpinnings; and potential for reproducibility. For each of the to a higher place-mentioned variables, a marking scheme with subcategories was applied, and the total score was calculated for each exercise to assess the level of bear witness for the effectiveness of interventions and models for community-based healthcare for migrants and refugees (Table 1). Each study was assessed according to the criteria set in an Excel file, and the total score was computed automatically as the improver of the subscores in each category.

No score threshold was gear up, as this was a comparative process amongst the interventions identified in this review. The higher the full score, the more than scientifically robust the proposed intervention was indicated.

iii. Results

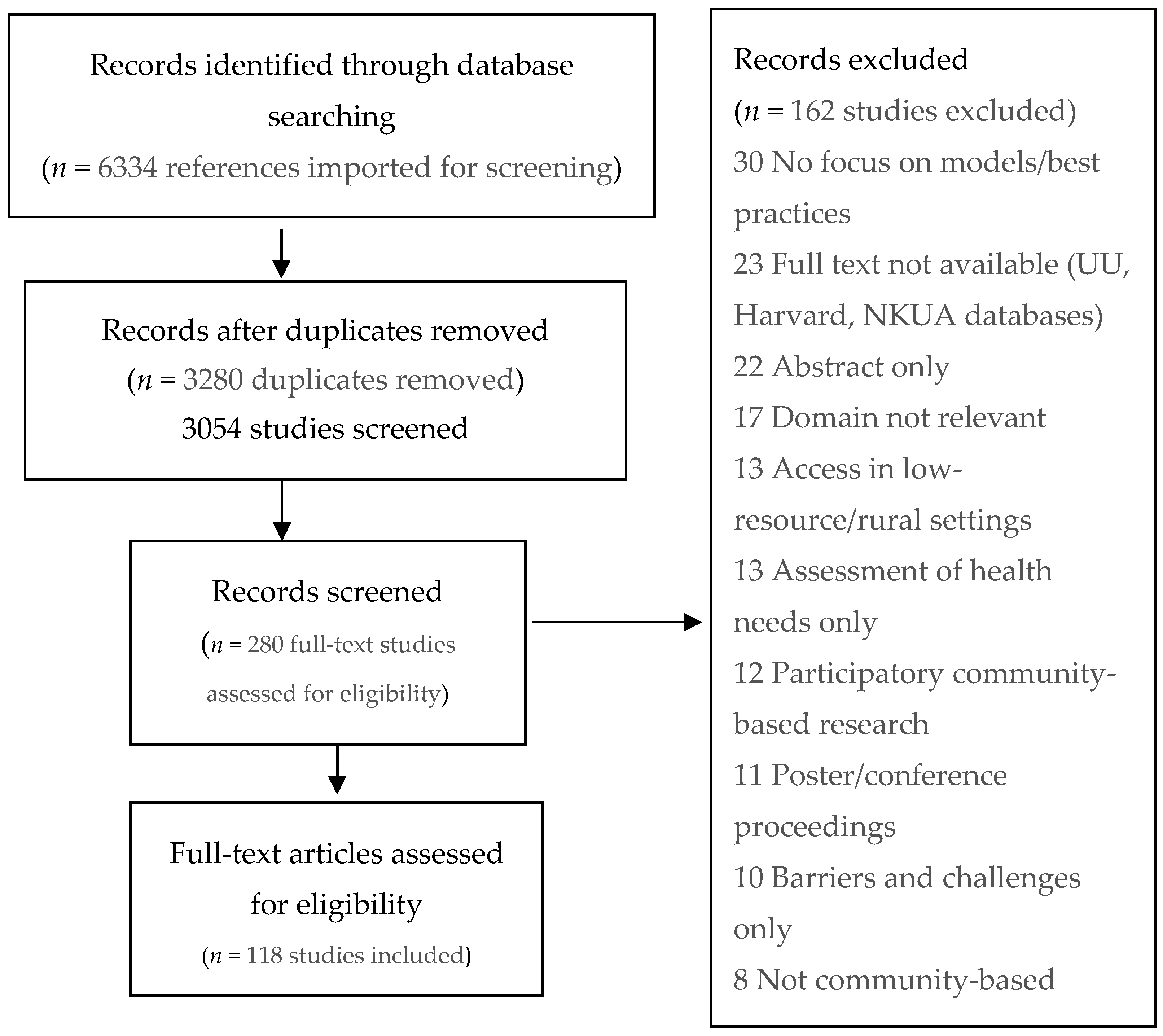

From our systematic database search, we retrieved 3054 unique records (Effigy 1). Close screening of titles and abstracts narrowed the total text number downwards to 280 publications, including 22 abstracts and briefing proceedings that were later removed every bit they were not followed by any total-text publication. Based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 118 publications remained for data extraction. A total overview of the selection procedure is presented in Effigy i.

3.one. Overall Study Characteristics

Out of 118 records, 53 (44.five%) discussed mental health, 36 (29.4%) community-based health services, 13 (10.nine%) noncommunicable diseases (excluding mental health), 9 (vii.6%) primary healthcare, and 7 (5.9%), maternal/women'southward health and child health.

Countries or regions of implementation included: North America (Usa and Canada), 67/118 (56.vii%), Europe, 28/118 (23.vii%), Australia and New Zealand, 9/118 (7.vi%), the Middle E, 6/118 (5.1%), Asia, 2/118 (ane.7%), and Latin America, i/118 (<1%). Five records did not specify the area of implementation. Populations targeted included migrants, immigrants, refugees, asylum-seekers, and racial and indigenous minorities, every bit defined by the respective authors. All these subgroups are function of the larger definition of migrants/refugees. Some publications targeted specific population groups such as women, children, adolescents, or families; elderly patients; trauma- or torture-exposed individuals; seasonal/subcontract workers; or individuals with a depression income. Ethnicity or country of origin of the target population groups was mentioned in some, but not all, publications. Study designs included mostly mixed methods (employ of quantitative and qualitative data); qualitative research (interviews and focus groups); surveys; and, less oft, experimental designs (controlled, randomized, or pre-postal service-test designs). Virtually experimental studies were labeled as pilot studies. Community aspects were framed equally either interventions implemented in the migrant community or as models or programs that rely on the engagement of different customs stakeholders (such as universities, schools, and dissimilar community health services). The vast majority of studies (105 out of 118) were published betwixt 2006 and 2018 (89%). A stardom between single and circuitous interventions was besides made. Past circuitous interventions, nosotros hateful activities (models or programs) that incorporate a number of component parts (interventions) with the potential for interactions between them that, when practical to the intended target population, produce a range of possible and variable outcomes [10]. Due to their nature, the effectiveness of complex interventions are more difficult to substantiate.

3.2. Identified Best Practices According to Thematic Area of the Reviewed Records

3.ii.1. Mental Health

Published interventions on mental health were carried out primarily in the U.s.a. (25/53), Europe (12/53), and Canada (eight/53) and less in the Middle East (ii/53), Australia (ii/53), and Asia (1/53). Dates of publication varied from 2002 to 2018, with 48/53 published in the flow of 2005–2017. Target populations involved refugees (in some studies, further specified as of particular descent, children, tortured, newly arrived, families, and multi-indigenous adults); minorities (elderly, ethnic, low-income, and racial); immigrants (traumatized children and adolescents, women, low-income, and of specific/varying descent); asylum-seekers; and migrants (of specific descent, youth, children, and families).

Single interventions described for community-based mental health services pertained to the training of (hereafter) healthcare workers and cultural brokering [11,12,thirteen,fourteen,fifteen,xvi,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,xl,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,lx,61,62,63]. Grooming programs refer to the cantankerous-cultural understanding and competency of healthcare workers [11,12] and the training and delivery of healthcare services among psychology or nursing students [fourteen,15]. In terms of "cultural brokering" [12], community peers [17,xviii,19,twenty,21], bilingual gatekeepers [22], and ethnic matching of therapists and patients [13,24] were identified. Complex interventions plant school-based programs to screen (and sometimes, also to treat) children and adolescents from migrant and refugee communities for mental health problems [xvi,25,26,27,28,29], mental health promotion in community day centers [30,31], and by customs organizations [32,33] and various other community-based mental health services [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Screening tools for psychosocial risk assessments were also used [20,42,43].

Core elements of the identified interventions and models were: partnering with members from target communities [44,45]; customs mobilization to stimulate outreach [33,46,47]; culturally and linguistically sensitive approaches [xiv,45,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]; didactics of health service providers on the needs of the target population [13,40,54]; sensation raising on mental health [46,55]; availability of information in relevant languages [44]; advocacy [56,57]; facilitating better integration [52]; responsiveness, coordination, and planning of different health and social services [12,54,55,58,59]; establishing a sense of belonging, community, and trust [xviii,58,59]; promoting empowerment and cultural competency [19,61,62]; funding [58]; and customs-based participatory enquiry [47].

iii.2.2. Wellness Services

Publications in this category are studies focusing on health promotion and access to intendance, mainly implemented in the USA (19/36), Europe (12/36), and Canada (ii/36), and in Commonwealth of australia (ii/36) and Asia (1/36), mostly in between 2007–2018 [64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,eighty,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99]. The populations addressed included racial and ethnic minorities; migrants (further specified every bit elderly, farm workers, or irregular); refugees (Syrian, flat-dwelling, youth, older developed, and more); immigrants (elderly or recent); and minority children. Information technology must be noted that the term "health services" in this review refers to all services related to health in general and not necessarily delivered within the healthcare arrangement of which principal wellness intendance is an integral part.

Single interventions that emerged constituted of: providing health information [64,65], cultural brokering through ambassadors [66,67,68,69,seventy,71,72], bilingual advocacy and interpretation [73,74], and a customs garden project addressing a sense of customs and adoption of a healthy dietary pattern [75]. Circuitous interventions, on the other hand, concerned community-academic partnerships [76,77,78,79,lxxx,81], customs-based nursing initiatives [82,83,84], home-based health services [83], programs on prevention, and healthcare services for the uninsured [85].

Prevalent aspects of interventions were: supervision and responsibility of stakeholders to provide equity, cultural, and linguistic competence in healthcare access and delivery [86,87]; creating a sense of community and delivery; obligation of stakeholders [68,86,87,88]; community-based leadership that is transferring the operational supervision of the intervention to the local level to facilitate sustainability [79,89]; social networking viewed as a necessary skill along with skillful communication to meliorate the efficiency of the intervention [89,ninety]; and show-based guidelines [91,92].

Additionally, reducing discrimination [92]; the promotion of understanding of human values [84,93]; targeted outreach strategies with specific focus on health education, wellness promotion, illness screening, and prevention [94]; community collaboration and advancement [74,88,91,93,94,95,96]; raising sensation on health risks [85,86,95]; and culturally and linguistically sensitive approaches [69,71,73,74,85,87,88,91,94,97,99].

Finally, building trust betwixt migrants and service providers [77,81,84], educating service providers on the wellness needs of the community [77,79,81,85,90], warranting the availability of resource [85,97] and sustainability of the programs [79,91], surveillance, and the evaluation of interventions [79,88,92].

3.2.three. Noncommunicable Diseases

Studies were conducted from 2012 to 2017 (12/thirteen) in the USA (5/13), Europe (2/xiii), multiple countries (ii/13), Canada, Australia, Heart E, and Latin America [100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112]. Target populations pertained to immigrants (more often than not women of various descents), refugees, migrants, and indigenous minorities, some of which were further divers as diabetic.

Customs-based strategies for the management of the post-obit were discussed: cancer screening [100,101,102,103,104], diabetes mellitus [99,105,106,107,108], cardiovascular affliction prevention [109,110], and other chronic diseases [111,112]. Cancer—generally breast cancer—prevention tools involved culturally tailored, narrative educational videos [100], pictograph-enhanced instructions [102], and patient-centered strategies [103,104]. The latter was too practical in diabetes mellitus management [106]. Diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease prevention interventions were culturally tailored approaches and story-telling [98,103,104,105,107,108,109].

Core elements of the described practices are culturally and linguistically sensitive education [103,104,109,112], involvement and support of the migrant communities' infrastructures [110], awareness-raising nigh wellness risks [101], outreach approaches through families and community peers [101,105,111], facilitating the "customs voice", intersectional collaboration, and funding [101].

3.2.4. Principal Healthcare

Publications in this expanse of activity were conducted mainly between 2012 and 2018 (7/9) in Australia (2/9), the USA (ii/ix), Canada (ii/nine), and the Middle East (i/9) (+2/ix not specified), and populations addressed included refugees and aviary-seekers, immigrants of various descents, and vulnerable migrants [113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121]. Aspects of the interventions in main healthcare discussed are appointment with the migrant customs through partnerships [113,114], stronger focus on ancillary services [121], interdisciplinary collaboration between public health and primary care institutions [116,117,118], culturally and linguistically trained interpreters [118,119], evidence-based guidelines [118,119], outreach activities by nurses [120], training of staff in cultural competency [114,121], health promotion education among migrants, and advocacy [117,121].

three.2.v. Maternal, Women'due south and Child Wellness

Six of the 7 identified records were carried out from 2001 to 2015 (i/7 in 1989) in the United states of america (iii/7), Commonwealth of australia (two/vii), Canada, and the Middle East (i/7). Target populations involved refugees (in certain studies, further defined as Syrian, children, and parents); immigrants; racial; and indigenous minority women [122,123,124,125,126,127,128].

The main focus of interventions in this area was the reduction of maternal and kid health inequalities among migrant/refugee communities, more often than not through publicly funded universal health activities [122] and government-led approaches [123]. Committed community and health service provider (agencies) partnerships through multiple mobilization strategies were considered successful for improving the wellness of significant women [124]. Capacity-building, as in ways to address barriers in healthcare provisions for minority populations, such as health insurance availability, healthcare toll reimbursement, healthcare advice in a native language, and culturally sensitive training of healthcare professionals, is essential; to maintain the interests of service providers and customs members is essential for program sustainability. In general, partnerships between the target community and the unlike local healthcare providers are recommended to identify the barriers faced by women and potential solutions for improving access to intendance [125]. Intensive child wellness promotion and instruction campaigns using ethnic media (radio, TV channels, and newsletters in the native language of the beneficiaries) and social networking were observed to positively affect parental sensation, knowledge, and behavior most communicable diseases prevention in children [126].

For individuals with additional wellness needs, such as those requiring prenatal or pediatric care, a Culturally Advisable Resources and Educational activity (C.A.R.East.) Clinic Health Advisor is recommended for specialty clinics. This type of health advisor facilitates advice, establishes a sense of community, and helps patients navigate the healthcare arrangement [127]. To implement reproductive health services in humanitarian emergencies, facilitators are a pre-existing operation health infrastructure, with prior training in their particular type of service commitment, dedicated leadership, and the availability of sufficient funding and resources [128].

3.iii. Promising All-time Practices at the Community Level

Our assessment prioritized the 15 acme all-time practices according to the ready criteria. The superlative scores were 20 points (1 publication), 19 points (1), 18 points (1), 17 points (4), 16 points (1), and 15 points (7 publications). These 15 interventions best fit the set evaluation criteria and are presented equally the about promising. In terms of the area of action, they are categorized every bit follows: 7 in mental health, ii in health service provision, ii in noncommunicable diseases, two in main healthcare, and 2 in maternal wellness (Table 2).

The training of health professionals, close collaborations of stakeholders, partnerships, social networks, linguistically and culturally sensitive service provisions, participatory approaches, and advocacy are elements described in these promising all-time practices.

iv. Give-and-take

This study reviewed the academic literature for best practices in customs healthcare models for migrants and refugees.

We adult an evaluation tool to assess and classify the search results for their scientific robustness based on their reported characteristics, such as population size, type of intervention, achieved outcome, reproducibility, and theoretical underpinning.

In the final gear up of identified practices, five areas of activeness were identified: mental health, wellness services, noncommunicable diseases, main healthcare, and maternal women's and child health. All publications were thoroughly assessed per category, and so, based on the evaluation ranking (a numerical score), the identified interventions/all-time practices were prioritized in terms of scientific soundness and reproducibility potential. Partnerships between governments and community providers, the design and commitment of tailor-made educational activities for children, linguistically and culturally adapted disease prevention activities, and community and school-based interventions for mental health addressing various population groups, as well as training programs for future healthcare professionals have been shown to be efficient and reproducible ways to improve the health of vulnerable population groups such equally refugees and migrants.

Challenges-Limitations

-

This review is a comprehensive try to identify customs-based best practices at the master healthcare level, addressing refugees and migrants in the peer-reviewed literature with the aim to provide information and guidance to the health professionals working at the master healthcare level primarily in the EU Member States. This endeavour encountered several challenges/limitations. In that location is an abundance of publications regarding interventions for migrant/refugee healthcare in the peer-reviewed literature. A huge variation in the significant of the terms community, community wellness or healthcare, and best practice was identified, forth with an interchangeable use of the terms migrants and refugees, also every bit immigrants, minorities, and aviary-seekers.

-

The majority of publications (64.3%) originated from the U.s.a., Canada, and Australia, addressing, past big, refugees and migrants at a much-progressed social integration stage compared to Europe and from very dissimilar ethnic backgrounds.

-

Many publications did not specify ethnicity; country of origin; or specific characteristics (i.e., age or social determinants) of the target population.

-

Despite the richness of published information, it should be noted that multiple other interventions exist that have not (and may never) been published through a peer-review process, due to numerous reasons spanning from lower prioritization of the health issue to lack of resources to encompass publications fees. Certainly, there tin can be areas of migrant/refugee health that could not be retrieved in the literature prior to March 2018, as no relevant publications were available. However, after reviewing some abstracts and conference proceedings, nosotros take strong reasons to believe that many interventions delivered as pilot studies have not been published every bit full-text papers, despite the fact that they provide valuable insights into potentially effective community-based interventions.

Plain, such problems are non of bottom importance compared to the published ones. In this aspect, it is important to note that studies on migrant/refugee health issues may never materialize into a peer-reviewed publication, as they often face several barriers such equally the scarcity of systematically recorded data on migrant/refugee health and a reluctance of vulnerable populations to participate in interventions stemming from communication difficulties to legal issues of residence and social exclusion, resulting in small participation rates and study samples or a difficulty in monitoring health in populations on the move, as they often change locations or even countries.

The objective of the present review was to identify the best practices and tools of community-based interventions for migrants/refugees, and equally such, a set of xv practices addressing the areas of mental health, primary healthcare, wellness service provision, and noncommunicable disease direction and prevention strategies, as well as maternal and child health, were identified based on specific evaluation criteria.

The majority of projects, activities, and interventions identified in this review focus on the area of mental health, and this is an important finding that needs to exist examined further, as in that location could be a multitude of reasons for this. The surface area of wellness service provision is as well important, as well every bit the issue of chronic disease management, which poses every bit a major time to come claiming for healthcare systems. The primary healthcare setting is vital, as it has shut links to the community and facilitates the involvement of the local population in preventing and managing diseases. It is of import to annotation that, in almost all of the sources identified, the elements of good communication, the linguistic barriers, and the cultural elements played crucial roles in the effective applications of the interventions. Evidently, the close collaborations of the diverse stakeholders, the local communities, the migrant/refugee communities, and the partnerships are key elements in the successful implementation of effective primary healthcare provisions.

v. Conclusions

The provision of essential health services of good quality for all population groups of a society is described in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [129]. These services, as emerged from our scoping review, include health promotion, disease prevention, and disease-management activities and should aim to meet the needs of all people, particularly migrants, refugees, and the vulnerable. Master healthcare services offered at the community level can cover all aspects of health-related needs and are very effective in addressing the health needs and challenges of all.

Writer Contributions

Eastward.R., conceptualization, methodology, publication choice and review, and evaluation criteria; S.K. (Shona Kalkman), search strategy, publication selection and review, and evaluation criteria; A.C., evaluation of mental wellness publications; S.Chiliad. (Sotirios Koubardas), original draft preparation; South.V., evaluation of primary healthcare and maternal and kid wellness publications; D.L., writing—Review and editing; P.K., project administration; D.Z., appraisal of best practices; M.Thousand., evaluation of noncommunicable diseases and of wellness service publications; T.P., writing—Review and editing; and A.L., funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This scoping review forms a part of the tasks described in the Eu projection "Strengthen Community Based Care to minimize wellness inequalities and meliorate the integration of vulnerable migrants and refugees into local communities". This project received fractional funding from the European Spousal relationship's Health Programme (2014–2020) Consumers, Wellness, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency (CHAFEA), Grant Agreement 738186, Acronym Mig-HealthCare.

Acknowledgments

The authors would similar to give thanks the Mig-HealthCare Partner Consortium (world wide web.mighealthcare.eu) for the fruitful collaboration in the project implementation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders (European Commission) had no part in the design of the written report; in the drove, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Un Loftier Committee for Refugees (UNHCR). Operational Data Portal. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- Matlin, S.A.; Depoux, A.; Schütte, S.; Flahaust, A.; Saso, L. Migrants' and refugees' health: Towards an agenda of solutions. Public Health Rev. 2018, 39, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe Report on the Health of Refugees and Migrants in the WHO European Region. No PUBLIC HEALTH without REFUGEE and MIGRANT HEALTH—Summary. 2018. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311348/9789289053785-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 17 Apr 2020).

- WHO Regional Part for Europe. Health Promotion for Improved Refugee and Migrant Health. Copenhagen; (Technical Guidance on Refugee and Migrant Health). 2018. Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/388363/tc-wellness-promotion-eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 (accessed on fourteen February 2020).

- MigHelthCare Minimize Health Inequalities and Amend the Integration of Vulnerable Migrants and Refugees into Local Communities. Bachelor online: https://world wide web.mighealthcare.european union/ (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Green, L.West.; Ottoson, J.One thousand. Community and Population Health, 8th ed.; WCB/McGraw-Colina: Boston, MA, U.s., 1999; Volume four, pp. 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, J.F.; Pinger, R.R.; Kotecki, J.E. An Introduction to Community Health; Jones and Bartlett Publishers: Boston, MA, U.s., 2005; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Un High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR). Refugees and Migrants. Available online: https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/definitions (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, Due south.L.; Rehfuess, East.A.; Smith, H.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Grimshaw, J.Thou.; Ford, Due north.P.; Portela, A. Circuitous health interventions in complex systems: Improving the process and methods for testify-informed health decisions. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e000963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baarnhielm, S.; Edlund, A.Southward.; Ioannou, 1000.; Dahlin, M. Approaching the vulnerability of refugees: Evaluation of cantankerous-cultural psychiatric preparation of staff in mental health care and refugee reception in Sweden. BMC Med. Educ. 2014, 14, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, T.; Connolly, A.M.; Klynman, N.; Majeed, A. Addressing mental health needs of asylum seekers and refugees in a London Borough: Developing a service model. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2006, 7, 249–256. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, D.E.; Overstreet, K.M.; Similar, R.C.; Kristofco, R.Eastward. Improving Depression Intendance for Indigenous and Racial Minorities: A Concept for an Intervention that Integrates CME Planning with Improvement Strategies. J. Contin. Educ. Wellness Prof. 2007, 27, S65–S74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondacaro, K.M.; Harder, 5.South. Connecting cultures: A grooming model promoting evidence-based psychological services for refugees. Railroad train. Educ. Prof. Psychol. 2014, 8, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, J.Yard.; Isakson, B.; Githinji, A.; Roche, N.; Vadnais, K.; Parker, D.P.; Goodkind, J.R. Reducing mental health disparities through transformative learning: A social alter model with refugees and students. Psychol. Serv. 2014, 11, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brar-Josan, N.; Yohani, S.C. Cultural brokers' part in facilitating informal and formal mental health supports for refugee youth in schoolhouse and community context: A Canadian case study. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 2017, 47, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnia, B. Refugees' Convoy of Social Back up: Community Peer Groups and Mental Health Services. Int. J. Ment. Health 2004, 32, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.; Rosenberg, R. Building Social Capital letter Through a Peer-Led Community Health Workshop: A Pilot with the Bhutanese Refugee Community. J. Customs Health 2016, 41, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieft, B.; Jordans, Chiliad.J.; de Jong, J.T.; Kamperman, A.M. Paraprofessional counselling within asylum seekers' groups in the netherlands: Transferring an approach for a not-western context to a European setting. Transcult. Psychiatry 2008, 45, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llosa, A.Due east.; Van Ommeren, M.; Kolappa, G.; Ghantous, Z.; Souza, R.; Bastin, P.; Slavuckij, A.; Grais, R.F. A two-stage arroyo for the identification of refugees with priority demand for mental health care in Lebanon: A validation written report. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, A.N.; Ornelas, I.J.; Kim, One thousand.; Perez, G.; Greenish, K.; Lyn, 1000.J.; Corbie-Smith, G. Results from a pilot promotora program to reduce depression and stress amidst immigrant Latinas. Health Promot. Psychol. 2014, 15, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-J. Effects of a Program to Meliorate Mental Health Literacy for Married Immigrant Women in Korea. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 31, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knipscheer, J.W.; Kleber, R.J. A need for ethnic similarity in the therapist-patient interaction? Mediterranean migrants in Dutch mental-health care. J. Clin. Psychol. 2004, lx, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowden, 50.; Masland, One thousand.; Ma, Y.; Ciemens, E. Strategies to ameliorate minority admission to public mental health services in California: Clarification and preliminary evaluation. J. Community Psychol. 2006, 34, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehler, Due south.; Birman, D.; Campbell, R. The Effectiveness of Cultural Adjustment and Trauma Services (CATS): Generating practice-based evidence on a comprehensive, schoolhouse-based mental health intervention for immigrant youth. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2012, 50, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiumento, A.; Nelki, J.; Dutton, C.; Hughes, G. School-based mental health service for refugee and aviary seeking children: Multi-agency working, lessons for proficient practice.Emerald Insight. J. Public Ment. Health 2011, 10, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.H.; Miller, A.B.; Abdi, S.; Barrett, C.; Claret, East.A.; Betancourt, T.S. Multi-tier mental wellness program for refugee youth. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 81, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, B.D.; Kataoka, S.; Jaycox, L.H.; Wong, M.; Fink, A.; Escudero, P.; Zaragoza, C. Theoretical footing and program design of a school-based mental health intervention for traumatized immigrant children: A collaborative enquiry partnership. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2002, 29, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrer, R.A.; Fazel, Thou. School and community-based interventions for refugee and asylum seeking children: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2014, ix, e97977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, 50.Eastward.; Rousseau, C. Ethnographic instance report of a community mean solar day center for aviary seekers as early on stage mental wellness intervention. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2018, 88, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gionakis, Due north.; Stylianidis, S. Community mental healthcare for migrants. In Social and Customs Psychiatry: Towards a Critical, Patient-Oriented Arroyo; Stylianidis, South., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arean, P.A.; Ayalon, L.; Jin, C.; McCulloch, C.East.; Linkins, K.; Chen, H.; McDonnell-Herr, B.; Levkoff, S.; Estes, C. Integrated specialty mental health care among older minorities improves admission but non outcomes: Results of the PRISMe study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2008, 23, 1086–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehn, Southward.D.; Jarvis, P.; Sandhra, S.Yard.; Bains, S.1000.; Addison, M. Promoting mental health of immigrant seniors in customs. Ethn. Inequalities Wellness Soc. Intendance 2014, seven, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birman, D.; Beehler, S.; Harris, Eastward.M.; Everson, 1000.L.; Batia, G.; Liautaud, J.; Frazier, S.; Atkins, One thousand.; Blanton, Due south.; Buwalda, J.; et al. International Family, Developed, and Child Enhancement Services (FACES): A customs-based comprehensive services model for refugee children in resettlement. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2008, 78, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dura-Vila, G.; Klasen, H.; Makatini, Z.; Rahimi, Z.; Hodes, One thousand. Mental health bug of young refugees: Elapsing of settlement, risk factors and community-based interventions. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2013, 18, 604–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltman, South.; Hurtado de Mendoza, A.; Serrano, A.; Gonzales, F.A. A mental health intervention strategy for low-income, trauma-exposed Latina immigrants in primary care: A preliminary study. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2016, 86, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltman, S.; Pauk, J.; Alter, C.L. Meeting the mental health needs of depression-income immigrants in chief care: A community adaptation of an bear witness-based model. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2011, 81, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, E.; Kim, Y.K.; Praetorius, R.T.; Mitschke, D.B. Mental health handling for resettled refugees: A comparison of three approaches. Soc. Work Ment. Wellness 2016, fourteen, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, South.; Divis, M.; Li, Y.B. Lucifer or mismatch: Use of the strengths model with chinese migrants experiencing mental disease: Service user and practitioner perspectives. Am. J. Psychiatr. Rehabil. 2010, 13, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.E.; Thompson, S.C. The use of community-based interventions in reducing morbidity from the psychological bear on of conflict-related trauma among refugee populations: A systematic review of the literature. J. Immigr. Minority Wellness 2011, 13, 780–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, H.; Bailey, R.; Jiang, West.; Aronson, R.; Strack, R. A pilot intervention for promoting multiethnic adult refugee groups' mental health: A descriptive article. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2011, 9, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Shakya, Y.B.; Li, J.; Khoaja, K.; Norman, C.; Lou, W.; Abuelaish, I.; Ahmadzi, H.M. A pilot with calculator-assisted psychosocial gamble-assessment for refugees. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2012, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polcher, Chiliad.; Calloway, Due south. Addressing the Need for Mental Health Screening of Newly Resettled Refugees: A Pilot Project. J. Prim. Intendance Customs Health 2016, 7, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Benbow, South.M. Mental health services for blackness and minority indigenous elders in the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: A systematic review of innovative practice with service provision and policy implications. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2013, 25, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, J.; Begley, C.; Culler, R. Evaluation of partner collaboration to improve community-based mental health services for depression-income minority children and their families. Eval. Program Plan. 2014, 45, 50–sixty. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, Thou.; Maxwell, C. A needs cess in a refugee mental health project in due north-e London: Extending the counselling model to community support. Med. Confl. Surviv. 2000, 16, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weine, S.G. Developing preventive mental health interventions for refugee families in resettlement. Fam. Process 2011, 50, 410–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, S. Multicultural mental wellness services: Projects for minority ethnic communities in England. Transcult. Psychiatry 2005, 42, 420–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, Northward.G.; Stein, K. Psychological Services for Asylum Seekers in the Community: Challenges and Solutions. Aust. Psychol. 2016, 51, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.B.; Hanner, J.A.; Cho, S.-J.; Han, H.-R.; Kim, M.T. Improving Access to Mental Health Services for Korean American Immigrants: Moving Toward a Community Partnership Between Religious and Mental Health Services. Psychiatry Investig. 2008, 5, xiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazzal, K.H.; Forghany, M.; Geevarughese, M.C.; Mahmoodi, V.; Wong, J. An innovative community-oriented approach to prevention and early intervention with refugees in the United states. Psychol. Serv. 2014, 11, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, O.A.; Ellis, B.H.; Escudero, P.V.; Huffman-Gottschling, K.; Sander, Grand.A.; Birman, D. Implementing trauma interventions in schools: Addressing the immigrant and refugee experience. Adv. Educ. Divers. Communities Res. Policy Prax. 2012, 9, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, 1000.; Guerraoui, Z.; Bonnet, Due south.; Gouzvinski, F.; Raynaud, J.P. Adapting services to the needs of children and families with circuitous migration experiences: The Toulouse University Infirmary'southward intercultural consultation. Transcult. Psychiatry 2017, 54, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, L.; Measham, T. Immigrants and mental health services: Increasing collaboration with other service providers. Can. Kid Adolesc. Psychiatry Rev. 2005, 14, 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Priebe, S.; Matanov, A.; Schor, R.; Straßmayr, C.; Barros, H.; Barry, M.; Díaz–Olalla, J.1000.; Gabor, E.; Greacen, T.; Holcnerová, P.; et al. Good exercise in mental wellness care for socially marginalised groups in Europe: A qualitative study of proficient views in 14 countries. BMC Public Health 2012, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodkind, J.R.; Hess, J.M.; Isakson, B.; LaNoue, G.; Githinji, A.; Roche, N.; Vadnais, K.; Parker, D.P. Reducing refugee mental health disparities: A community-based intervention to address postmigration stressors with African adults. Psychol. Serv. 2014, xi, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, South. The role of a clinical director in developing an innovative believing community treatment squad targeting ethno-racial minority patients. Psychiatr. Q. 2007, 78, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, L.; Jaimes, A.; Johnson-Lafleur, J.; Rousseau, C. Perspectives of Migrant Youth, Parents and Clinicians on Customs-Based Mental Health Services: Negotiating Prophylactic Pathways. J. Kid Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 1936–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijbrandij, M.; Acartürk, C.; Bird, Yard.; Bryant, R.A.; Burchert, S.; Carswell, K.; De Jong, J.; Dinesen, C.; Dawson, Thou.Due south.; El Chammay, R.; et al. Strengthening mental health care systems for Syrian refugees in Europe and the Middle Due east: Integrating scalable psychological interventions in viii countries. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2017, 8, 1388102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, K.E.; Davidson, G.R.; Schweitzer, R.D. Review of refugee mental wellness interventions post-obit resettlement: Best practices and recommendations. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2010, 80, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.Y.B.; Li, A.T.; Fung, Thousand.P.; Wong, J.P. Improving Access to Mental Wellness Services for Racialized Immigrants, Refugees, and Not-Status People Living with HIV/AIDS. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2015, 26, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, M.B.; McGregor, B.; Thandi, P.; Fresh, E.; Sheats, K.; Belton, A.; Mattox, K.; Satcher, D. Toward culturally centered integrative care for addressing mental wellness disparities amongst indigenous minorities. Psychol. Serv. 2014, xi, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, J.; Russo, A.; Block, A. The Refugee Health Nurse Liaison: A nurse led initiative to improve healthcare for asylum seekers and refugees. Contemp. Nurse 2016, 52, 710–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortinois, A.A.; Glazier, R.H.; Caidi, N.; Andrews, G.; Herbert-Copley, M.; Jadad, A.R. Toronto'south two-1-ane healthcare services for immigrant populations. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 43, S475–S482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutcher, G.A.; Scott, J.C.; Arnesen, S.J. The refugee health information network: A source of multilingual and multicultural health information. J. Consum. Health Net 2008, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, T.R.W. "Community ambassadors" for South Asian elder immigrants: Late-life acculturation and the roles of community health workers. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 1769–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, T.; Wills, J. Engaging with marginalized communities: The experiences of London health trainers. Perspect. Public Health 2011, 132, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesselink, A.Eastward.; Verhoeff, A.P.; Stronks, One thousand. Indigenous Health Care Advisors: A Expert Strategy to Improve the Access to Wellness Intendance and Social Welfare Services for Ethnic Minorities? J. Community Health 2009, 34, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejic, V.; Hess, R.S.; Miller, G.E.; Wille, A. Family offset: Customs-based supports for refugees. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2016, 86, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shommu, Due north.S.; Ahmed, S.; Rumana, N.; Barron, G.R.Southward.; McBrien, Chiliad.A.; Turin, T.C. What is the telescopic of improving immigrant and indigenous minority healthcare using community navigators: A systematic scoping review. Int. J. Equity Wellness 2016, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhagen, I.; Ros, W.J.; Steunenberg, B.; de Wit, N.J. Culturally sensitive care for elderly immigrants through ethnic community health workers: Pattern and development of a customs based intervention programme in the Netherlands. BMC Public Wellness 2013, 13, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhagen, I.; Steunenberg, B.; de Wit, N.J.; Ros, W.J. Community wellness worker interventions to meliorate access to health care services for older adults from ethnic minorities: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ansari, W.; Newbigging, K.; Roth, C.; Malik, F. The office of advancement and estimation services in the commitment of quality healthcare to diverse minority communities in London, United Kingdom. Health Soc. Care Community 2009, 17, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.S.; Kagawa-Vocalist, M. Increasing access to care for cultural and linguistic minorities: Ethnicity-specific wellness intendance organizations and infrastructure. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2007, xviii, 532–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggert, L.K.; Claret-Siegfried, J.; Champagne, One thousand.; Al-Jumaily, M.; Biederman, D.J. Coalition Building for Wellness: A Community Garden Pilot Project with Apartment Dwelling Refugees. J. Community Health Nurs. 2015, 32, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chocolate-brown, N.J.; Barton, J.A. A collaborative effort betwixt a land migrant health programme and a baccalaureate nursing programme. J. Community Health Nurs. 1992, nine, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, A.; Rainer, 50.P.; Simcox, J.B.; Thomisee, G. Increasing the commitment of health intendance services to migrant farm worker families through a customs partnership model. Public Health Nurs. 2007, 24, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodkind, J.R.; Githinji, A.; Isakson, B. Reducing Health Disparities Experienced by Refugees Resettled in Urban Areas: A Community-Based Transdisciplinary Intervention Model. In Converging Disciplines; Kirst, 1000., Schaefer-McDaniel, Due north., Hwang, S., O'Campo, P., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, Us, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, D.Chiliad.; Becker, D.M.; Bone, L.R.; Colina, G.N.; Tuggle, M.B.; Zeger, Due south.L. Community-academic health center partnerships for underserved minority populations. One Solut. A Natl. Crisis. JAMA 1994, 272, 309–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, J.South.; Castañeda, H. Delivery of mobile clinic services to migrant and seasonal farmworkers: A review of practice models for community-academic partnerships. J. Customs Health 2013, 38, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissman, Grand.E.; Morris, R.J.; Ng, C.; Pozzessere, A.Southward.; Scott, K.C.; Altshuler, One thousand.J. Global wellness at home: A student-run community health initiative for refugees. J. Wellness Care Poor Underserved 2012, 23, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, D.Chiliad. Caring for the Unseen: Using Linking Social Upper-case letter to Improve Healthcare Access to Irregular Migrants in Kingdom of spain. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2016, 48, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, Southward.One thousand.; Liebel, D.; Wilde, G.H.; Carroll, J.Thousand.; Zicari, E.; Chalupa, South. Meeting the Needs of Older Adult Refugee Populations With Home Wellness Services. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2016, 28, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifi, R.A.; Makhoul, J.; El Hajj, T.; Nakkash, R.T. Developing a logic model for youth mental wellness: Participatory enquiry with a refugee community in Beirut. Wellness Policy Plan. 2011, 26, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priebe, S.; Sandhu, S.; Dias, S.F.; Gaddini, A.; Greacen, T.; Ioannidis, Eastward.; Kluge, U.; Krasnik, A.; Lamkaddem, M.; Lorant, V.; et al. Proficient practice in health care for migrants: Views and experiences of care professionals in 16 European countries. BMC Public Health 2011, eleven, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aluko, Y. Carolinas Association for Community Health Equity-Enshroud: A community coalition to accost health disparities in racial and ethnic minorities in Mecklenburg County N Carolina. In Eliminating Healthcare Disparities in America; Williams, R.A., Williams, R.A., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw-Taylor, Y. Culturally and linguistically appropriate health intendance for racial or indigenous minorities: Analysis of the US Office of Minority Health's recommended standards. Wellness Policy 2002, 62, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladovsky, P.; Ingleby, D.; McKee, Thousand.; Rechel, B. Good practices in migrant health: The European experience. Clin. Med. 2012, 12, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumiel-Berhalter, 50.M.; Kahn, 50.; Watkins, R.; Goehle, M.; Meyer, C. The implementation of Good For The Neighborhood: A participatory community health program model in iv minority underserved communities. J. Customs Health 2011, 36, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawde, N.C.; Sivakami, G.; Babu, B.Five. Building Partnership to Improve Migrants' Admission to Healthcare in Bombay. Front. Public Health 2015, 3, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, 1000. Devising, implementing, and evaluating interventions to eliminate wellness intendance disparities in minority children. Pediatrics 2009, 124, S214–S223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottie, K.; Hui, C.; Rahman, P.; Ingleby, D.; Akl, E.A.; Russell, G.; Ling, 50.; Wickramage, One thousand.; Mosca, D.; Brindis, C.D. Building Responsive Health Systems to Assist Communities Affected by Migration: An International Delphi Consensus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, fourteen, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barenfeld, E.; Gustafsson, S.; Wallin, 50.; Dahlin-Ivanoff, S. Understanding the "black box" of a health-promotion plan: Keys to enable health among older persons aging in the context of migration. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Existence 2015, 10, 29013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devillé, W.; Greacen, T.; Bogić, G.; Dauvrin, One thousand.; Dias, Due south.F.; Gaddini, A.; Jensen, N.1000.; Karamanidou, C.; Kluge, U.; Mertaniemi, R.; et al. Health care for immigrants in Europe: Is there still consensus amongst land experts about principles of good practice? A Delphi study. BMC Public Wellness 2011, eleven, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barenfeld, E.; Gustafsson, South.; Wallin, L.; Dahlin-Ivanoff, S. Supporting decision-making by a health promotion plan: Experiences of persons ageing in the context of migration. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2017, 12, 1337459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrera, G.J. Integrating Principles of Positive Minority Youth Development with Health Promotion to Empower the Immigrant Customs: A Case Study in Chicago. J. Customs Pract. 2017, 25, 504–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paoli, L. Access to health services for the refugee community in Greece: Lessons learned. Public Wellness 2018, 157, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health and Human being Services. Refugee and Aviary Seeker Health Services- Guidelines for the Customs Health Programme. 2015. Available online: https://refugeehealthnetwork.org.au/refugee-and-asylum-seeker-health-services-guidelines-for-the-community-health-program (accessed on 14 Feb 2020).

- Philis-Tsimikas, A.; Gallo, L.C. Implementing Community-Based Diabetes Programs: The Scripps Whittier Diabetes Plant Experience. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2014, 14, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornelas, I.J.; Ho, K.; Jackson, J.C.; Moo-Young, J.; Le, A.; Do, H.H.; Lor, B.; Magarati, M.; Zhang, Y.; Taylor, V.K. Results From a Pilot Video Intervention to Increment Cervical Cancer Screening in Refugee Women. Health Educ. Behav. Off. Publ. Soc. Public Wellness Educ. 2018, 45, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Jandu, B.; Albagli, A.; Angus, J.E.; Ginsburg, O. Exploring ways to overcome barriers to mammography uptake and memory amongst Southward Asian immigrant women. Health Soc. Care Customs 2013, 21, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. Development and airplane pilot exam of pictograph-enhanced chest health-care instructions for community-residing immigrant women. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2012, xviii, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escribà-Agüir, Five.; Rodríguez-Gómez, M.; Ruiz-Pérez, I. Effectiveness of patient-targeted interventions to promote cancer screening among ethnic minorities: A systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016, 44, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirazi, M.; Shirazi, A.; Blossom, J. Developing a culturally competent faith-based framework to promote chest cancer screening among Afghan immigrant women. J. Relig. Health 2015, 54, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzubaidi, H.; Mc Namara, Grand.; Browning, C. Time to question diabetes self-management support for Arabic-speaking migrants: Exploring a new model of care. Diabet. Med. A J. Br. Diabet. Assoc. 2017, 34, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, G.N.; Mclean, Y.; Byers, S.; Taylor, H.; Braizat, O.M. Combined Diabetes Prevention and Disease Self-Management Intervention for Nicaraguan Indigenous Minorities: A Pilot Study. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Activity 2017, 11, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieland, Yard.L.; Njeru, J.W.; Hanza, M.Chiliad.; Boehm, D.; Singh, D.; Yawn, B.P.; Patten, C.A.; Clark, G.M.; Weis, J.A.; Osman, A.; et al. Stories for change: Airplane pilot feasibility project of a diabetes digital storytelling intervention for refugee and immigrant adults with blazon two diabetes. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, S319. [Google Scholar]

- Zeh, P.; Sandhu, H.M.; Cannaby, A.Chiliad.; Sturt, J.A. The touch on of culturally competent diabetes care interventions for improving diabetes-related outcomes in ethnic minority groups: A systematic review. Diabet. Med. A J. Br. Diabet. Assoc. 2012, 29, 1237–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, A.; Musshauser, D.; Sahin, F.; Bezirkan, H.; Hochleitner, Thou. The Mosque Campaign: A cardiovascular prevention program for female Turkish immigrants. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2006, 118, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Vijver, Southward.; Oti, S.O.; Van Charante, E.P.M.; Allender, South.; Foster, C.; Lange, J.; Oldenburg, B.; Kyobutungi, C.; Agyemang, C. Cardiovascular prevention model from Kenyan slums to migrants in the Netherlands. Glob. Wellness 2015, 11, xi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, Due south.; Jonsson, R.; Skaff, R.; Tyler, F. Community-Based Noncommunicable Disease Care for Syrian Refugees in Lebanon. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2017, five, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddaiah, R.; Roberts, J.E.; Graham, L.; Piddling, A.; Feuerman, M.; Cataletto, 1000.B. Customs health screenings can complement public health outreach to minority immigrant communities. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2014, 8, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, I.-H.; Wahidi, Southward.; Vasi, Southward.; Samuel, Southward. Importance of customs engagement in primary health care: The instance of Afghan refugees. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2015, 21, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin-Zamir, D.; Keret, South.; Yaakovson, O.; Lev, B.; Kay, C.; Verber, G.; Lieberman, N. Refuah Shlema: A cantankerous-cultural programme for promoting communication and health among Ethiopian immigrants in the primary health care setting in Israel: Evidence and lessons learned from over a decade of implementation. Glob. Health Promot. 2011, 18, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, R. Main health intendance for refugees and asylum seekers: A review of the literature and a framework for services. Public Wellness 2006, 120, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurray, J.; Breward, K.; Breward, One thousand.; Alder, R.; Arya, N. Integrated primary care improves access to healthcare for newly arrived refugees in Canada. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2014, 16, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, C.; Hall, South.; Elmitt, Due north.; Bookallil, Grand.; Douglas, Thousand. People-centred integration in a refugee primary intendance service: A complex adaptive systems perspective. J. Ournal Integr. Care 2017, 25, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottie, K.; Batista, R.; Mayhew, M.; Mota, L.; Grant, K. Improving commitment of primary treat vulnerable migrants: Delphi consensus to prioritize innovative practise strategies. Can. Fam. Doctor 2014, 60, e32–e40. [Google Scholar]

- Griswold, K.Southward.; Pottie, G.; Kim, I.; Kim, West.; Lin, L. Strengthening effective preventive services for refugee populations: Toward communities of solution. Public Wellness Rev. 2018, 39, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElmurry, B.J.; Park, C.G.; Buseh, A.Thousand. The nurse-community health advocate team for urban immigrant principal health care. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. Off. Publ. Sigma Theta Tau Int. Award Soc. Nurs. 2003, 35, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Cho, H.-I.; Cheon-Klessig, Y.S.; Gerace, L.M.; Camilleri, D.D. Primary health care for Korean immigrants: Sustaining a culturally sensitive model. Public Health Nurs. 2002, 19, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelland, J.; Riggs, East.; Szwarc, J.; Casey, South.; Dawson, W.; Vanpraag, D.; Eastward, C.; Wallace, Eastward.; Teale, M.; Harrison, B.; et al. Bridging the Gap: Using an interrupted time series design to evaluate systems reform addressing refugee maternal and child health inequalities. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchins, V.; Walch, C. Meeting minority health needs through special MCH projects. Public Health Rep. 1989, 104, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bhagat, R.; Johnson, J.; Grewal, S.; Pandher, P.; Quong, Eastward.; Triolet, Chiliad. Mobilizing the community to address the prenatal wellness needs of Immigrant Punjabi women. Public Health Nurs. 2002, xix, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, S.; Camacho, D.; Freund, K.M.; Bigby, J.; Walcott-McQuigg, J.; Hughes, Eastward.; Nunez, A.; Dillard, W.; Weiner, C.; Weitz, T.; et al. Women's wellness centers and minority women: Addressing barriers to care. The National Centers of Excellence in Women's Health. J. Women's Health Gend. Based Med. 2001, ten, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, M.; MacIntyre, C.R. The touch of intensive wellness promotion to a targeted refugee population on utilisation of a new refugee paediatric clinic at the children'south hospital at Westmead. Ethn. Health 2009, xiv, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reavy, Chiliad.; Hobbs, J.; Hereford, M.; Crosby, K. A new dispensary model for refugee wellness care: Accommodation of cultural safety. Rural Remote Health 2012, 12, 1826. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, Due south.; Williams, H.A.; Onyango, M.A.; Sami, S.; Doedens, W.; Giga, Northward.; Rock, E.; Tomczyk, B. Reproductive wellness services for Syrian refugees in Zaatri Camp and Irbid City, Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan: An evaluation of the Minimum Initial Services Package. Confl. Health 2015, nine, S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Evolution. Available online: http://www.united nations.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=Eastward (accessed on 15 April 2020).

Figure ane. PRISMA period diagram for Mig-HealthCare systematic database search.

Figure one. PRISMA catamenia diagram for Mig-HealthCare systematic database search.

Table one. Evaluation criteria of selected interventions on community-based best practices.

Table i. Evaluation criteria of selected interventions on customs-based best practices.

| Study Design | Sample Size (n) | Elapsing of Follow-Up | Eye Eastern/North African Individuals Included in Target Population | Reported Outcomes/Or Advocate Evidence-Backed Approach | Reproducible (As Mentioned in Publication) | Theoretical Underpinning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 = not specified | NA = not applicable | NA = not applicable | 1 = no | 1 = no | 1 = not mentioned | NA = not applicable |

| 1 = review/clarification (no data) | 1 = <x | C = cross-exclusive design | ii = yes | 2 = aye | 2 = can be reproduced | 1 = non present in publication |

| 2 = qualitative or quantitative data | 2 = xi–fifty | 1 = days | 2 = presented in publication | |||

| 3 = mixed methods | three = 51–100 | 2 = weeks | ||||

| iv = experimental study (randomized, controlled, or pre-post-test blueprint) | four = > 100 or ≤ ten papers (for reviews) | 3 = months | ||||

| 5 = literature review | v = > grand or > 10 papers (for reviews) | 4 = ane–5 years | ||||

| P = pilot study | v = > five years |

Table 2. The fifteen highly assessed all-time practices.

Table two. The fifteen highly assessed all-time practices.

| Publication | Reference Number | Expanse of Intervention | Intervention | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| McMurray (2014) | [116] | Primary healthcare | Partnership betwixt a dedicated health dispensary for authorities-assisted refugees, a local reception center, and community providers | 20 |

| Reavy (2012) | [127] | Maternal health | New clinic model for prenatal and pediatric refugee patients (in particular, the part of the Culturally Appropriate Resource and Education (C.A.R.E.) Clinic Health Counselor) | nineteen |

| Small (2016) | [38] | Mental health | Comparison of three different treatment modalities: handling as usual (TAU), dwelling-based counseling (HBC), and a customs-based psycho-educational grouping (CPG) | 18 |

| Bader (2006) | [109] | Noncommunicable Diseases | Linguistically and culturally sensitive cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention program | 17 |

| Sheikh & McIntyre (2002) | [126] | Maternal health | Intensive kid health promotion and educational activity entrada using ethnic media and social network | 17 |

| Williams & Thompson (2011) | [40] | Mental wellness | Community-based mental healthcare services | 17 |

| Kaltman (2011) | [37] | Mental health | Collaborative mental healthcare program implemented in a network of primary care clinics that serve the uninsured | 17 |

| Fondacarro (2016) | [xiv] | Mental wellness | Preparation program for psychology students ("Connecting Cultures") | 16 |

| Levin-Zamir (2011) | [114] | Principal healthcare | Cross-cultural program for promoting communication and health | 15 |

| Siddaiah (2014) | [112] | Noncommunicable Diseases | Community-based, culturally competent respiratory wellness screening and teaching | xv |

| Tumiel-Behalter (2011) | [89] | Health service provision | Community plan with a participatory approach to ameliorate the health of four underserved communities ("Skilful For The Neighborhood") | 15 |

| Ferrera (2017) | [96] | Health service provision | Wellness promotion initiative that integrates principles of positive minority youth development | 15 |

| Tyrer & Fazel (2014) | [29] | Mental health | School and community-based interventions | 15 |

| Kaltman (2016) | [36] | Mental wellness | Mental health intervention for primary intendance clinics that serve the uninsured | 15 |

| Goodkind (2014) | [56] | Mental wellness | Community-based advancement and learning intervention with refugees and undergraduate students | xv |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This commodity is an open admission article distributed nether the terms and weather of the Creative Eatables Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9032/8/2/115/htm

,

,

0 Response to "Barriers to Health Care Access for Low Income Families: a Review of Literature."

Post a Comment